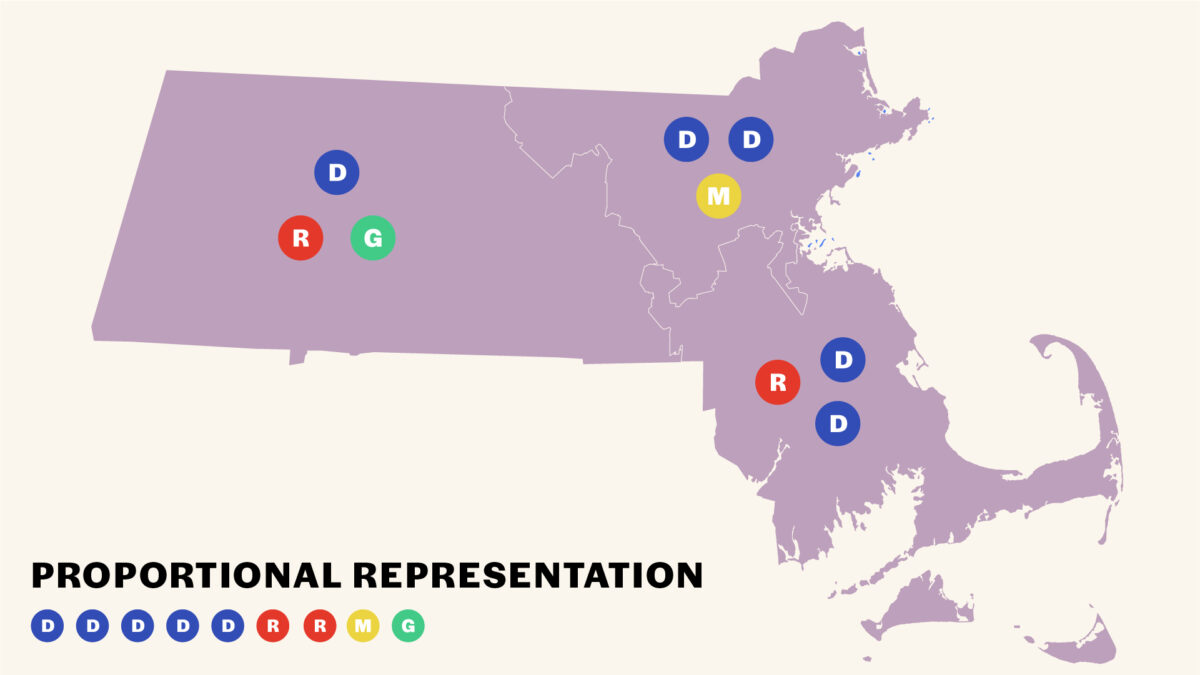

Proportional representation is an electoral system that elects multiple representatives in each district in proportion to the number of people who vote for them. If one third of voters back a political party, the party’s candidates win roughly one-third of the seats. Today, proportional representation is the most common electoral system among the world’s democracies.

How is this different from what the United States uses?

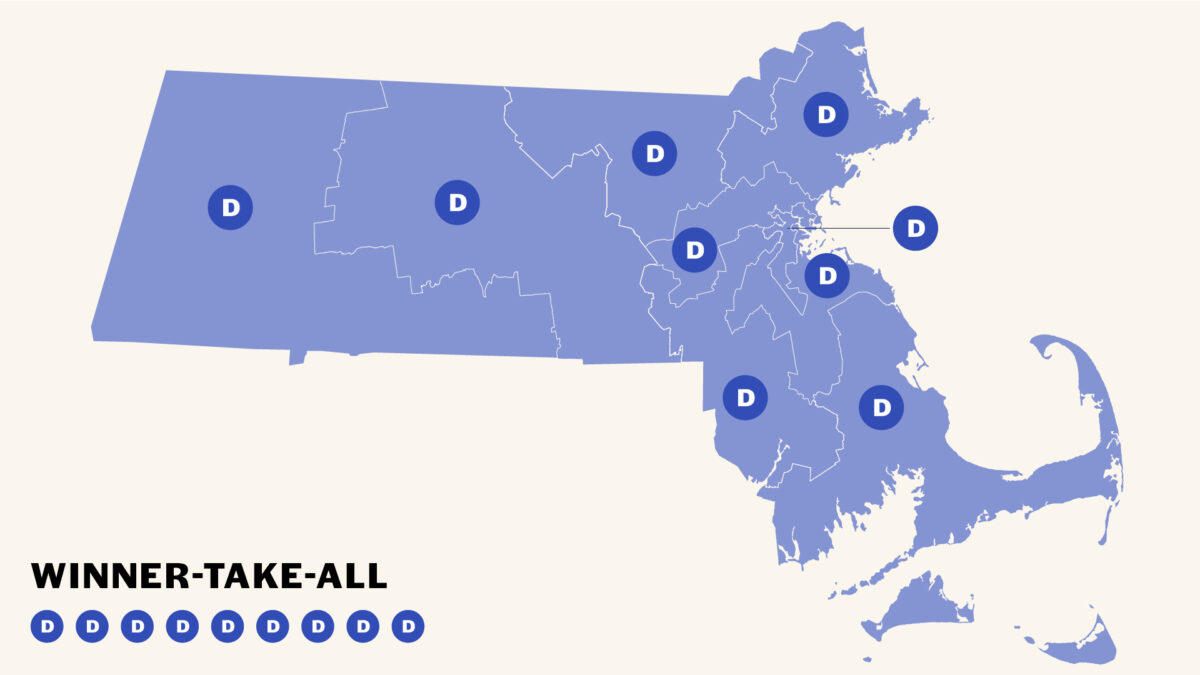

Every American today lives in a district that elects a single representative for congressional and most state legislative elections. Voters cast a vote for a candidate, one candidate wins, and all the others lose. This makes our elections “winner-take-all” — if a candidate wins 51 percent of the vote, she wins 100 percent of the representation. Any voters who did not back the winning candidate are not represented in government by a candidate for whom they voted.

Read more: How open are Americans to electoral system reform? Read more: How open are Americans to electoral system reform?

In contrast, proportional representation uses multi-seat districts with representation allocated in proportion to votes. For example, in a six-seat district, if a party’s candidates win 51 percent of the vote, they would be expected to win three of the six seats — rather than 100 percent. Unlike with winner-take-all, under proportional representation, most groups tend to have at least one elected official representing their viewpoint in government.

According to scholarly research, winner-take-all elections are causing or aggravating some of the most pressing problems undermining American democracy. These include:

Biasing outcomes →With winner-take-all, 51 percent (and sometimes less) of the electorate wins 100 percent of the representation in a district. This leads to unrepresentative outcomes. For example, despite a third of Massachusetts reliably voting Republican, Democrats control all nine U.S. House seats. Likewise, in Oklahoma, while a third of the electorate votes for Democrats, all five of its House seats are Republican.

Gerrymandering →Winner-take-all systems are uniquely susceptible to gerrymandering. But in proportional systems, manipulating district lines for partisan gain is often functionally impossible — multi-winner districts are simply too difficult to gerrymander. Want to get rid of gerrymandering? Adopt a system of proportional representation.

Disadvantaging minority voices →Winner-take-all elections uniquely disadvantage racial, ethnic, religious, and other political minorities, especially when they do not live in geographically concentrated areas and with district lines deliberately drawn around them. By contrast, minority representation tends to improve under proportional systems by allowing groups to win representation in proportion to their numbers, regardless of where they live.

Stifling competition →Because winner-take-all elections make it easy for a single party to dominate in a district, they tend to depress political competition. As soon as a party can count on 55-60% of the vote, a district becomes “safe.” Except in a small number of swing districts, competition shifts to low-turnout primaries where candidates tend to be pulled to the extremes. By contrast, proportional systems tend to be more competitive: with more seats in contention per district, more parties and their candidates are incentivized to compete.

Exacerbating polarization →Winner-take-all systems tend to produce two-party systems, which are more likely to increase affective polarization — meaning voters from opposing parties don’t just disagree with one another, but come to reflexively distrust and dislike one another. Because multi-winner races create space for more than two parties, proportional representation tends to produce more fluid coalitions, which research finds helps to temper polarization.

Escalating extremism →By definition, winner-take-all elections are high stakes. Marginal differences in support for either of two parties can mean total victory or total defeat. Politicians are often incentivized to do everything they can to beat their opponents, even at the expense of problem solving, good governance, or maintaining democratic norms. Voters and politicians who lose in winner-take-all elections are less likely to trust democratic institutions, and more likely to resort to violence.

Researchers are especially concerned about the use of winner-take-all elections in highly polarized and diverse societies like the United States. As one global study of democratization concluded, “if any generalization about institutional design is sustainable,” it is that winner-take-all electoral systems “are ill-advised for countries with deep ethnic, regional, religious, or other emotional and polarizing divisions.”

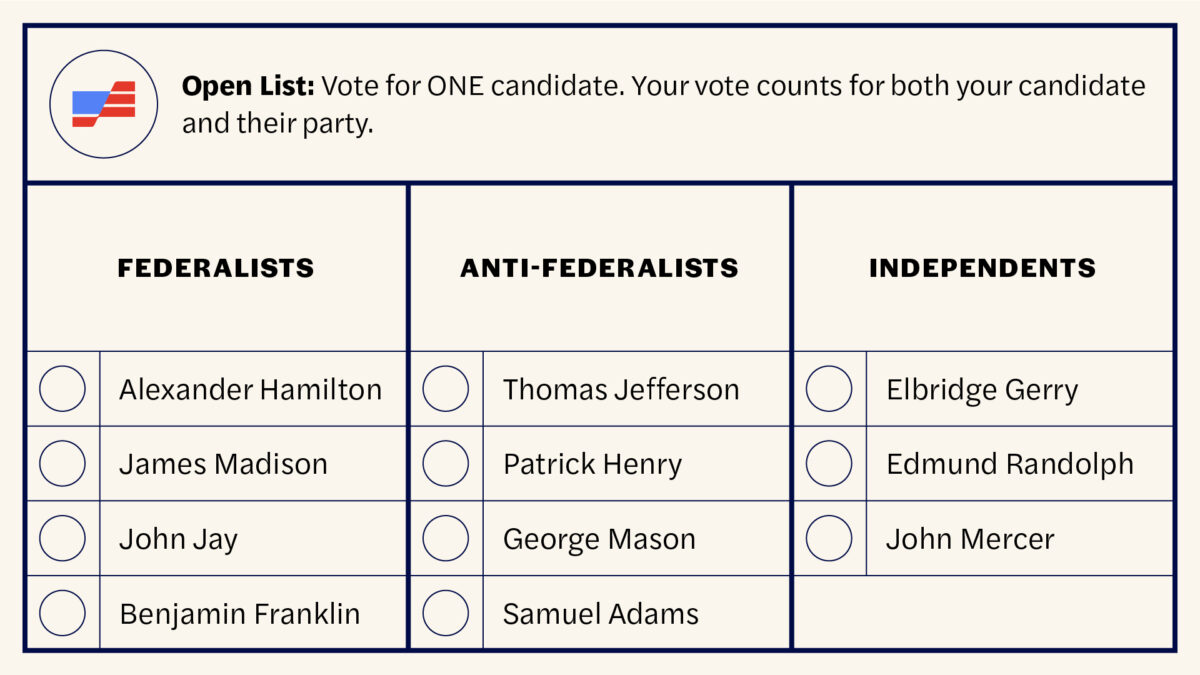

Think: Voting for a candidate and their party

In open list systems, each political party has a slate of candidates running for office (as in a primary election), and voters choose a candidate from one of the lists. Parties are allocated seats in proportion to the total number of votes their candidates receive, and the candidates who receive the most votes are elected. For example, a voter may select one Democrat from a list of Democrats running. In a six-seat district, if the Democrats together win 50 percent of the vote, the three Democratic candidates with the most votes are elected.

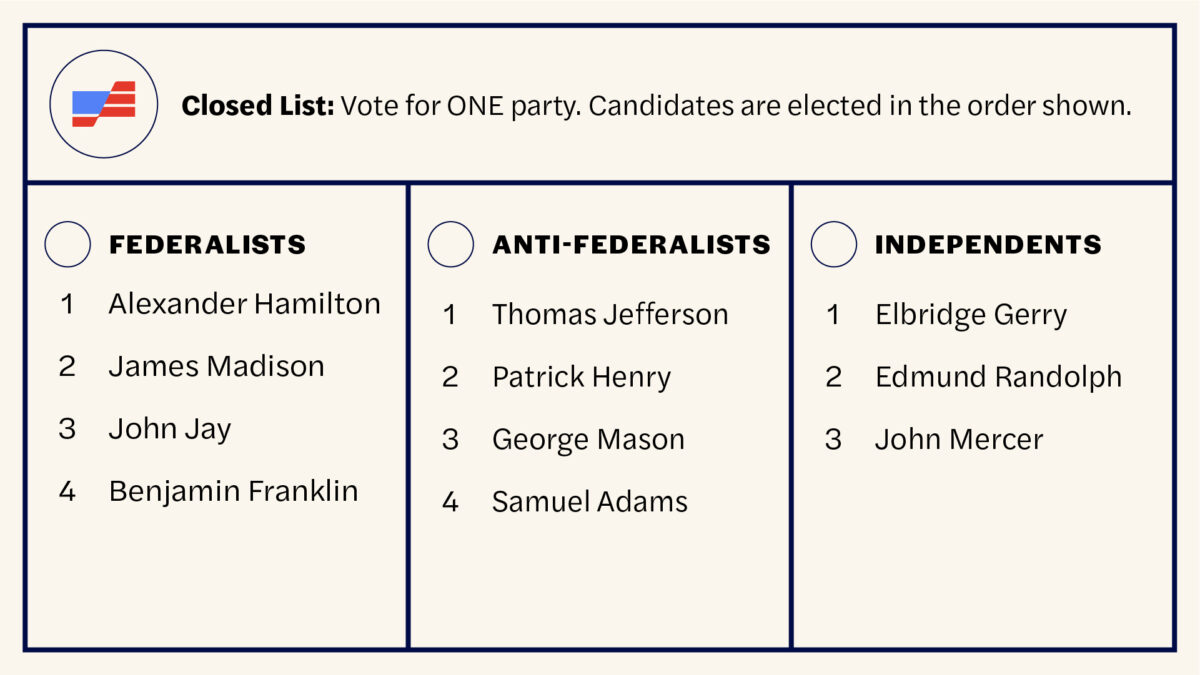

Think: Voting for a party, not for a candidate

In closed list systems, voters select a political party on a ballot rather than an individual candidate. Parties are allocated seats in proportion to the votes they receive, and candidates are seated in the order determined by the party itself. For example, a voter may select the Republican Party on the ballot, but not an individual candidate. In a six-seat district, if Republicans win 50 percent of the vote, the party is allocated three seats, and the top-three candidates on the party’s list are elected.

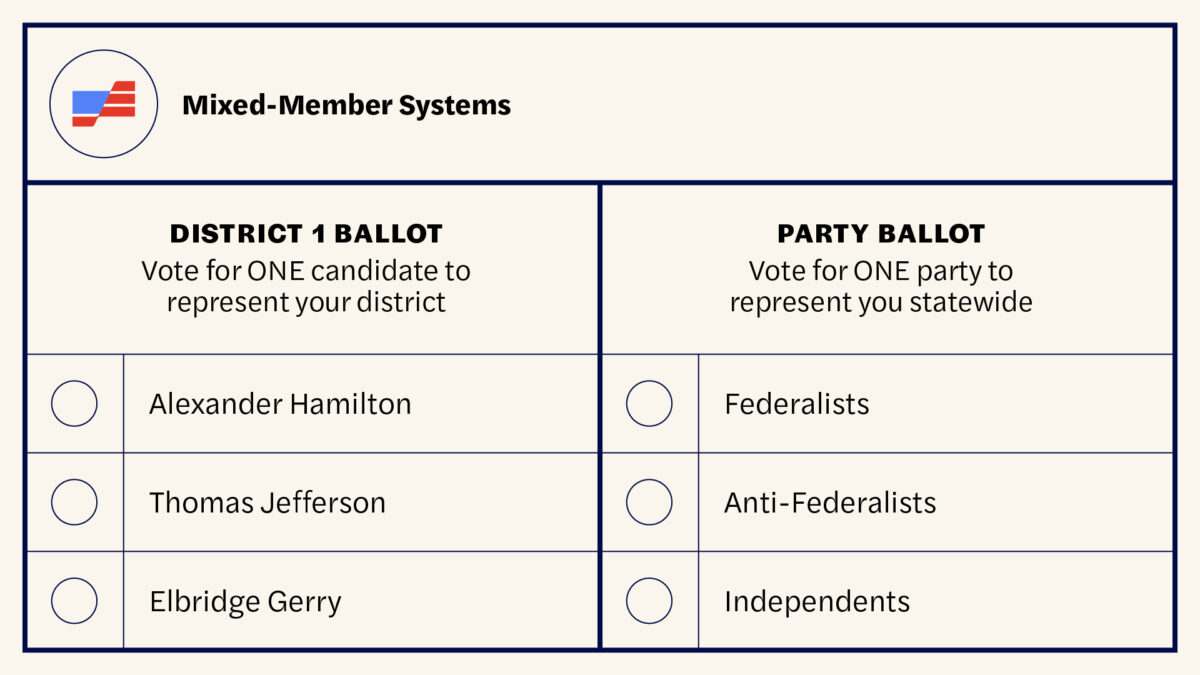

Think: Proportional representation layered on top of single-member districts

Many countries use systems that blend components of winner-take-all and proportional representation, combining single-member districts with some number of additional seats allocated to parties proportionally. Voters make two choices: one for their single-winner district and one for a set of statewide seats allocated proportionally. For example, a given state could have three single-winner districts and three proportional seats. A party that gets 40% of the vote statewide could lose all three single-winner seats but still win one or two of the proportional seats.

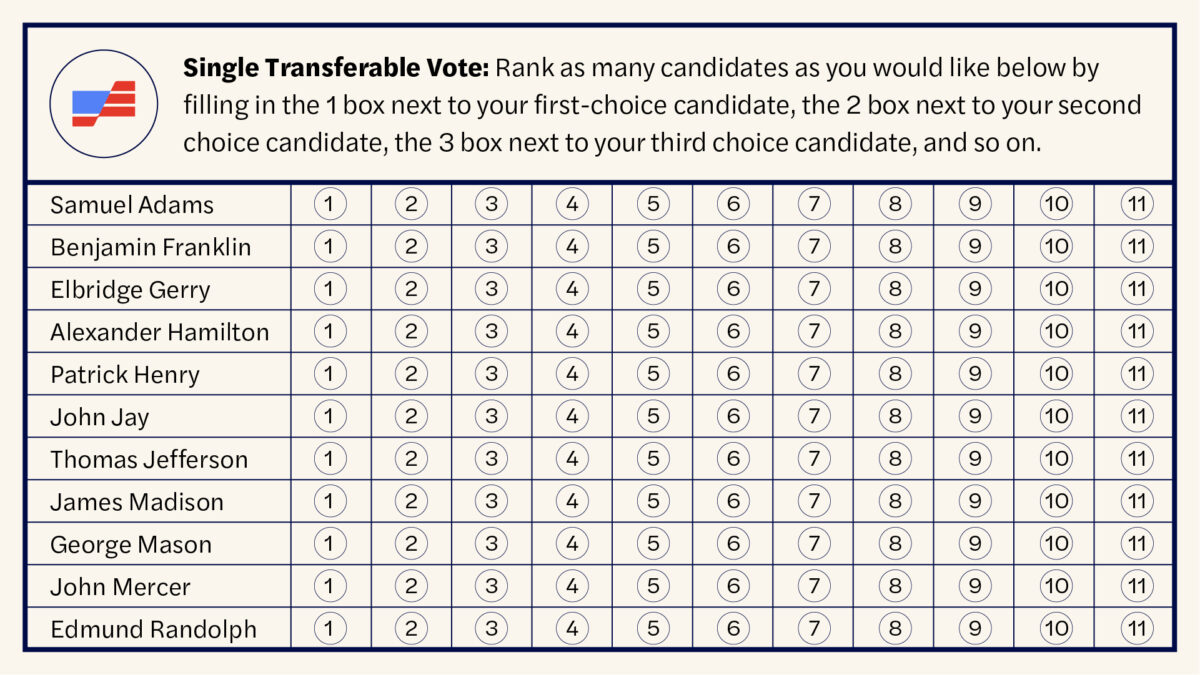

Think: Ranking candidate choices across the ballot

Some countries use a system where voters rank candidates, regardless of their party, and the top-ranked candidates are elected. Through successive rounds of ballot counting, votes are reallocated to lower preferences as candidates are either elected or eliminated. This goes on until the seats are filled. For example, if a voter’s first choice candidate comes in last, the candidate is eliminated and the vote is reallocated to the voter’s next preference in the next round of counting. Additionally, if a candidate gets more than the amount of votes needed to win a seat, the additional votes are also reallocated to the voters’ lower preferences.